Dr Kevin Brianton

Senior Lecturer, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

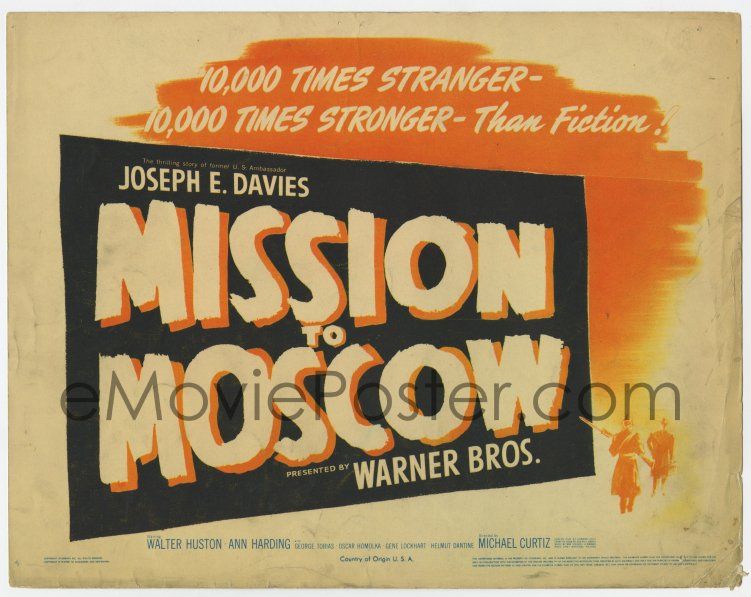

Image courtesy of eMoviePoster.

The MPAPAI’s efforts were reinforced by the studio heads’ desire to crush the studio unions and the obtain political favour with the emerging Republican and McCarthyite forces. The efforts of the alliance were not wasted. The conflict between the ultra-conservatives and the radicals came to a head at the HUAC hearings into communist involvement in Hollywood on 20 October 1947. The Washington-based committee planned to interview both communist and anti-communist witnesses for the next 10 days.

In January 1947, studio head Jack Warner had received a Medal of Merit from the Federal government for his work in government training films, yet in October his studio was being investigated for subversion.[1] With the Republicans in control of Congress since the 1946 elections, it was clear that the political pendulum was moving toward the right and Hollywood was one of the first targets. The committee lined up several ultra-conservative leaders in Hollywood to begin the investigation.

HUAC has also subpoenaed 19 Hollywood producers, directors and writers as unfriendly witnesses. Eleven of these had worked for Warner Brothers, the studio which produced the most wartime propaganda and had aligned itself with the Roosevelt administration. The studio had also been prominent for its ‘social conscience’ films of the 1930s.[2] The HUAC investigations had a special reason for singling out the Warner Brothers studio, for its film, Mission to Moscow, as it was based on the work of Davies, a prominent member of the Roosevelt administration. If they could establish a link between the White House and the production of the pro-Russian pictures of the Second World War, it could cause the Truman administration enormous political damage, the type that was to occur later with the Alger Hiss trial.

Studio head Jack Warner assured the committee that no subversive propaganda had ever made it to the screen, not even in Mission to Moscow. He was initially forthright in his defence of his studio. Warner told the committee that if making Mission to Moscow in 1942 was a subversive activity, then so too were ‘the American Liberty ships and naval conveys which carried food and guns to Russian allies’.[3] Warner defended Mission to Moscow as being necessary because of the danger that Stalin would make a treaty with Hitler if Stalingrad fell. Such an alliance would lead to the destruction of the world.[4] The film was designed to cement the friendship between the USSR and the United States in a desperate time.

Following studio heads Jack Warner and Louis B. Mayer came novelist Ayn Rand, who was considered by the committee to be an expert witness on the Soviet Union. Her expertise was derived from her Russian origins and right-wing views. Rand viewed Song of Russia for the committee and described at length its inaccuracies, failings and lies. Her criticism of the film clustered around the depiction of Russian peasant life. She said that at least three and a half million, possibly seven million people, had died from starvation in the drive to collectivization of farms and the film makes no mention of them.[5] Rand said the depiction of Soviet village life was ridiculous. Women were dressed in attractive blouses and shoes. She said if any person had the food shown in the film in the Ukraine, they would have been murdered by starving people attempting to get food.[6] Rand summed up her position on pro-Russia films like Song of Russia saying it was unnecessary to deceive the American people about the Soviet Union.

Say it is a dictatorship, but we want to be associated with it. Say it is worth being associated with the devil, as Churchill said, in order to defeat another evil which is Hitler. There may be a good argument for that. But why pretend that Russia is not what it was.[7]

The hearings were highly unpopular at this state and the New York Times wrote in an editorial saying that the investigation was unfair and could lead to greater dangers than it was fighting.[8] In Hollywood, the Committee for the First Amendment was formed by writer Phillip Dunne, directors John Huston and William Wyler and actor Alexander Knox to oppose censorship of films and to prevent a blacklist.[9]

The group had a massive backing and took out huge advertisements in trade newspapers. The Committee for the First Amendment wanted the Hollywood 19, as they were known, to take the first amendment, and do nothing else. Instead, when the unfriendly witnesses were called they tried to answer the committee’s questions in their own way which led to shouting matches in the hearings. The first unfriendly witness, screenwriter John Howard Lawson, attempted to yell down the committee saying it was on trial before the American people. When he was finally dragged from the stand, he set a precedent for the remaining witnesses. Other witnesses were simply asked if they had ever been a member of the Communist Party. When they failed to answer, they were charged with contempt.

On the 19 subpoenaed, ten were called before the committee and refused to testify citing constitutional rights of privacy and freedom of political thought and association. Screenwriter and playwright Bertolt Brecht denied all knowledge of the communist party and later fled the country. For unknown reasons, Chairman Parnell Thomas cancelled the hearings before the remaining nine were heard.

The

Hollywood 10, as they became known, were sent to prison for contempt of

congress and the rest were blacklisted from work in Hollywood.[10] The group, along with most legal experts at

the time, believed that their contempt charges would be overturned in the

Supreme Court on the constitutional ground of the right to hold private

political beliefs.[11] Unfortunately for the Hollywood 10, two

liberal judges died before their cases were heard and they were replaced by

conservatives. The deaths changed the

political composition of the Supreme Court which then backed the contempt

citations. This decision by the Supreme

Court opened the legal door for the McCarthyite era. People were now in the position of taking

either the fifth amendment protecting them against self incrimination and

facing blacklisting and other harassment, or informing on people with communist

views.

[1] New York Times, 27 January 1947.

[2] Richard Maltby, ‘Made for Each Other: The Melodrama of Hollywood and the House Committee on Un-American Activities’ in Phillip Davies and Brian Neve, (eds.). Cinema, Politics and Society in America, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1981, p. 87.

[3] US Congress, House Committee on Un-American Activities, Hearings Regarding the Communist Infiltration of the Motion Picture Industry, 80th Congress, 1st sess., 20 October 1947, vol. 1169 (5) p.10.

[4] ibid., p. 34.

[5] HUAC Hearings, p. 85.

[6] Ibid., p.85.

[7] HUAC Hearings., p.89.

[8] New York Times, 23 October 1947.

[9] The signatories to the Committee for the First Amendment were Larry Adler, Stephen Morehouse Avery, Geraldine Brooks, Roma Burton, Lauren Bacall, Barbara Bentley, Leonardo Bercovici, Leonard Berstein, DeWitt Bodeem, Humphrey Bogart, Ann and Moe Braus, Richard Brooks, Jerome Chodorov, Cheryl Crawford, Louis Calhern, Frank Callender, Eddie Canto, McClure Capps, Warren Cowan, Richard Conte, Norman Corwin, Tom Carlyle, Agnes DeMille, Delmar Davesm Donald Davies, Spencer Davies, Donald Davis, Armand Deutsch, Walter Doniger, I.A.L. Diamond., L. Diamond, Muni Diamond, Kirk Douglas, Jay Dratler, Phillip Dunne, Howard Duff, Paul Draper, Phoebe and Harry Ephron, Julius Epstein, Phillip Epstein, Charles Einfeldm Sylvia Fine, Henry Fonda, Melvin Frank, Irwin Gelsey, Benny Goodman, Ava Gardner, Sheridan Gibney, Paulette Goddard, Michael Gordon, Jay Goldberg, Jesse J. Goldburg, Moss Hart, Rita Hayworth, David Hopkins, Katherine Hepburn, Paul Heinreid, Van Heflin, John Huston, John Houseman, Marsha Hunt, Joseph Hoffman, Uta Hagen, Robert L. Joseph, George Kaufman, Norman Krasna, Herbert Kline, Michael Kraike, Isobel Katleman, Arthur Lubin, Mary Loss, Myrna Loy, Burgess Meredith, Richard Maibaum, David Millerm Frank L. Moss, Margo, Dorothy McGuire, Ivan Moffat, Joseph Mischel, Dorothy Matthews, Lorie Niblio, N. Richard Nash, Doris Nolan, George Oppenheimer, Ernest Pascal, Vincent Price, Norman Panama, Marion Parsonnet, frank Partos, Jean Porter, John Paxton, Bob Presnell Jr., Gregory Peck, Harold Rome, Gladys Robinson, Francis Rosenwald, Irving Rubine, Irving Reis, Stanley Hubin, Slyvai Richards, Henry C. Rogers, Lyle Rooks, Norman and Betsy Rose, Robert Ryan, Irwin Shaw, Richard Sale, George Seaton, John Stone, Allan Scott, Barry Sullivan, Shepperd Sturdwick, Mrs Leo Spitz, Theodore Strauss, John and Mari Shelton, Robert Shapiro, Joseph Than, Leo Townsend, Don Victor, Bernard Vorhaus, Billy Wilder, Bill Watters, Jerry Wald and Cornel Wilde. Myron C. Fagan Documentation of Red Stars in Hollywood printed in Gerald Mast The Movies in Our Midst: Documents in the Cultural History of film in America, 2nd edn., Oxford University Press, New York, 1979, p. 549.

[10] The Hollywood Ten were screenwriters John Howard Lawson, Alvah Bessie, Dalton Trumbo, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Ring Lardner Jr; the writer-producer Herbert Biberman; the writer-producer Adrian Scott; and the director Edward Dymytryk.

[11] Hollywood on Trial, (d) David Helpern Jr, Annie Resman.