Kevin Brianton

Senior Adjunct Research Fellow, La Trobe University, Melbourne

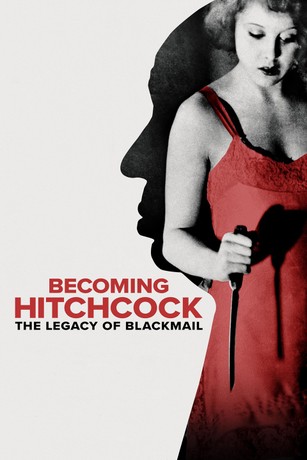

Becoming Hitchcock: The Legacy of Blackmail (2022) holds a unique and important place within Hitchcock scholarship. The feature-length documentary examines Blackmail (1929), Hitchcock’s first sound film. This movie is now seen as a key work of British cinema. However, as the title suggests, Bouzereau’s project argues that many of Alfred Hitchcock’s signature directing techniques were developed with this film.

The most obvious criticism of the documentary is that Blackmail was not his first Hitchcockian film. In the 1920s, Hitchcock worked on many different types of films, but the origin of the title “Master of Suspense” is often associated with The Lodger (1926). Hitchcock himself considered it his first film in the genre that would define his career. Many agree with him. The film historian Henry K. Miller has championed The Lodger as his starting point, most recently in the book of essays Re-Viewing Hitchcock (2025), describing it as “Hitchcock’s First True Movie.” The essay is based on his book, The First True Hitchcock: The Making of a Filmmaker, (2022). In this essay, Miller outlines numerous critics over the decades who argued along similar lines. For example, Paul Rotha, in the influential The Film Till Now (1930), saw the pair of films as key stepping stones in Hitchcock’s development. In sharp contrast to these views, Bouzereau offers a compelling counterpoint through this documentary.

The film’s plot centres on Alice White, played by Anny Ondra, the daughter of a London shopkeeper, who quarrels with her police detective boyfriend, Frank Webber, played by John Longden. In a rebellious mood, she goes out with a charming artist, Mr. Crewe, played by Cyril Ritchard, who takes her to his studio. When he tries to rape her, Alice kills him in self-defense with a bread knife. The next day, the body is discovered, and Frank is assigned to investigate the murder. He finds Alice’s glove at the scene and realizes she is the killer. He secretly covers up that evidence. However, a petty criminal named Tracy, played by Donald Calthrop, witnesses Alice with the artist and gets the other glove as proof. He tries to blackmail both Alice and Frank. When Tracy’s scheme falls apart, he is suspected of the murder. A dramatic chase happens through the British Museum. The film ends with Tracy’s accidental death and an uneasy resolution: Alice feels she must confess to the authorities, but she is stopped at the last moment. Frank and Alice must face the consequences of their obstruction of justice, leaving their future uncertain.

Hitchcock’s early work is explored through this documentary, revealing various aspects of his emerging cinematic talent. The first part focuses on the transition from silent to sound cinema. Blackmail was released in both versions since it was made right at this pivotal moment in 1929. Hitchcock’s impressive ability to adapt to new technology is clear in the film’s most famous scene, where Alice hears a neighbour’s gossip that gradually becomes a distorted chorus repeating the word “knife.” Despite the challenges of this awkward new technology, Hitchcock showed he could be innovative. Others faced even greater difficulties. The female lead, Anny Ondra, had a strong Czech accent, so she had to be dubbed for the sound version. Ultimately, she moved to Germany to continue her acting career.

The documentary then shifts to other recurring themes in Hitchcock’s films that would dominate his cinema for the next 40 years. The first theme was that of an accused, but innocent person. The documentary shows that, starting with this work, themes of personal guilt emerge and are projected onto others. Alice’s guilt is indirectly transferred when her boyfriend, a Scotland Yard detective, frames the blackmailer for the murder. A blurred line then exists between justice and vigilante action. In Blackmail, the “hero” breaks the law, complicating the moral landscape. In his later work, Hitchcock repeatedly questions the nature of crime and punishment. In Dial M for Murder (1954), the husband plans the “perfect crime,” and almost defeats the legal system. In Strangers on a Train (1951), Bruno acts on Guy’s suppressed desire. In Psycho (1960), Norman Bates disposes of a body to protect his ‘mother.’

Alice becomes caught in a web of shame and fear while another innocent person is hunted. This theme is arguably central to Hitchcock’s work. From The 39 Steps (1935) through to North by Northwest (1959), Hitchcock enjoyed placing an ordinary individual in extraordinary, dangerous situations where they are wrongly accused or implicated. The documentary shows that these ideas re-emerge in I Confess (1953), where a priest bears guilt for a murder. In Vertigo (1958), another police detective, Scottie, falsely feels guilt over Madeleine’s death while being manipulated by others.

Two final points support the idea that it is Hitchcock’s first true film. Alice is almost certainly the prototype of the “Hitchcock Blonde.” She is attractive, takes a risk by entering the artist’s studio, and her actions drive the entire story. Alice is a more vulnerable, morally complex character caught in a web of her own making. The documentary examines the famous scene where Alice is assaulted by the artist, which, for the time, nearly crossed the boundaries of sexual violence. It marks the beginning of the glamorous, elegant, often cold or mysterious blonde, a figure central to the film’s themes of danger and desire: Madeleine/Judy in Vertigo, Eve Kendall in North by Northwest, and Melanie in The Birds. They are both objects of fascination and threats.

The first use of landmarks in a climactic chase occurred in this film, a technique that would become a staple of his cinema. In Blackmail, it takes place on the dome of the British Museum, a public landmark, which is transformed into a tense, surreal arena for a chase and a death. His fellow director, Michael Powell, claims some credit for suggesting the idea. Hitchcock would go on to famously use iconic locations to heighten suspense: Mount Rushmore and the United Nations building in North by Northwest, and the Statue of Liberty in Saboteur (1942).

In the documentary, Blackmail serves as a blueprint for the Hitchcock universe. It highlights his central obsession: the fragility of ordinary life and how quickly a simple decision can turn a person into a nightmare of guilt, accusation, and moral confusion, all conveyed through a masterful, subjective visual style. Overall, the film emphasizes the idea of an auteur’s work. The title Becoming Hitchcock is straightforward, implying a destined path for the British director. This perspective overlooks the more chaotic, chance-driven nature of artistic growth. Opportunities appeared, and Hitchcock seized them fully. The influence of writers, actors, and camera operators is quietly downplayed. While his wife Alma Reville, producers, and screenwriters are mentioned, the documentary’s narrative focuses on Hitchcock’s individual genius overcoming all obstacles. For film students, it offers an engaging introduction to the foundational elements of Hitchcock’s cinema. Bouzereau’s Becoming Hitchcock: The Legacy of Blackmail is a well-crafted piece of popular film history that succeeds in its primary goal: establishing Blackmail as the foundational text of Hitchcock’s career and demonstrating, with compelling visual evidence, the development of his signature style.

A note on availability: Blackmail was restored in 2024, building on earlier preservation work. Bouzereau’s documentary is featured on DVD sets of Hitchcock’s silent films, on various streaming platforms. It has been broadcast on channels like TCM. It was screened at the British Film Festival at Palace Cinemas in Australia.