Image from eMoviePoster

Kevin Brianton

Senior Lecturer, La Trobe University

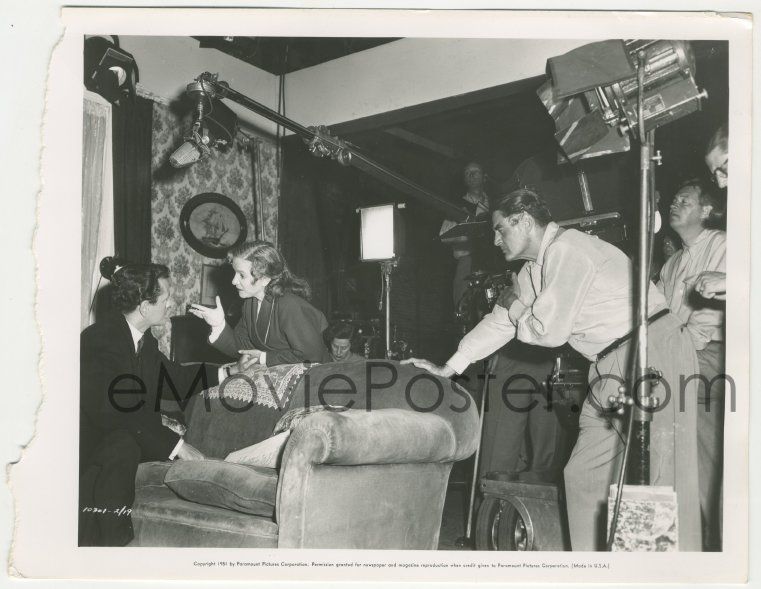

The links between sexuality and communism were seen in other films, but none more pointed than My Son John (1952) which linked political subversion to sexual activity. Producer, writer and director Leo McCarey was one of the leading anti-communist campaigners in Hollywood,[1] and his film My Son John was a serious attempt to alert America to, what he considered, a dangerous and pressing threat. McCarey was a staunch anti-Communist and had joined Wood in testifying to HUAC in October 1947. He had directed Going My Way (1944) and The Bells of St. Marys (1945), which were very popular films with Bing Crosby as Father O’Malley. McCarey told HUAC his films were not successful in Russia because they contained God. He wanted Hollywood to produce anti-Communist films as it had done in the Second World War against fascism. In 1952, McCarey would do just that and direct one of the more feverish anti-Communist films in My Son John – the final political messages of which were fashioned by DeMille. The film seemed to have absorbed the political tensions of Hollywood during that strained time. From its opening scenes, it was a gloomy tense depiction of strangling the American family.

Image courtesy of eMoviePoster.

The film witnessed the return of Helen Hayes – the first lady of american Theatre – after 18 years away from the screen. The story began as Ben and Chuck Jefferson, played by James Young and Richard Jaeckel, went off to fight in the Korean War. They were blonde clean-cut American boys who played football, while their brother John, played by Robert Walker, was dark haired and read books. John worked at some mysterious job in Washington. Their mother, played by Helen Hayes, was distressed that he did not return for their farewell party. When he did return, Hayes was shocked to learn that he scoffed at his father’s membership of the American Legion. Suspicions increased when he told his parents that he believed that Bible stories should be taken on a symbolic rather than literal level.

With the evidence mounting fast, his mother Lucille, played by Helen Hayes, made John swear on the Bible that he was not a communist. He was quite happy to oblige because he was an atheist and was not afraid of eternal damnation by making such an oath. The Bible was also used in a scene where John’s father Dan sang John a song he composed for his American Legion Friends.

If you don’t like you’re Uncle Sammy;

Then go back to the your home o’er the sea;

To the land from where you came;

Whatever its’ name;

But don’t be ungrateful to me;

If you don’t like the stars in Old Glory;

If you don’t like the red, white and blue;

Then don’t act like he cur in the story;

Don’t bite the hand that’s feeding you.[2]

He then bashed John over the head with the bible when he laughed. The scene appeared to be strongly influenced by a similar scene from Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 version of The Ten Commandments, where a mother read the story of Exodus from the bible to her two sons. One son also scoffed at the reading and was struck over the head by the other son with a newspaper. In an earlier draft of the screenplay of My Son John, the father struck John when he scoffed at the commandment about honoring your parents. The similarity was no accident as DeMille’s political speech writer Donald Hayne wrote the original drafts for the final speech by John Jefferson.[3] To scoff at the ten commandments was the equivalent of extolling communism for DeMille who saw them as the moral basis to fight communism.[4] Furthermore, to scoff was direct proof of communist tendencies, hence the father’s righteous and violent reaction.

Image courtesy of eMoviePoster

DeMille exercised absolute control over his staff and it would be impossible to believe that Hayne wrote the speech without DeMille’s direction, approval and consent. DeMille’s writers considered themselves to be ‘trained seals’ who merely translated the director’s thoughts onto paper.[5] Even though he has not listed in the credits, it is clear that DeMille had a great deal of power within Hollywood’s anti-communist community and that power extended to influencing the anti-communist content of films of other directors.

John’s father Dan, played by Dean Jagger, swore that if he even thought his son was a communist, he would take him into the back yard and shoot with a double-barrel shotgun. McCarey’s depiction of the all-American father was drunk, violent, and stupid. Throughout the film, the father was extremely hostile to John’s intellectual achievements, and yet the mother’s character was even worse. She hovered on the edge of a nervous breakdown and there were several hints to her being menopausal. In an earlier draft of the film, the message was clear that she was going through a ‘stage of life’ and needed to constantly take pills.[6] When the mother heard that John was being investigated by the FBI for being communist, she regarded it as solid evidence that he was guilty. In the draft script, she actually collapsed before testifying that her son was a communist. The audience was meant to conclude that her communist son was undermining her mental and physical health. It would be easier to believe that these demented parents led their children into communism.

Like I Married a Communist, My Son John linked intellectual activity to communism. John was constantly compared with his blonde brothers. They played football and were doing their patriotic duty in Korea while John was an intellectual and a traitor. T seemed failure to play football was one of the key elements of becoming a political subversive. The mother recalled going to a football game to see Ben and Chuck play. As she supported their football team, she would turn to John and barrack for him in his own personal football game. The audience was told that John’s brothers were pulled out of school to pay for John’s education. These ideas neatly fitted with the anti-intellectual atmosphere of the McCarthyite investigators. It was a time when the word ‘egghead’ became a pejorative term for intellectuals.[7] While making the film, McCarey told The New York Times:

(My Son John) is about a mother and father who struggle and slaved. They had no education. They put all their money into higher education for their sons. But on of the kids gets too bright. It poses the problem – how bright can you get?

He takes up a lot of things including atheism… The mother only knew two books – her Bible and her cookbook. But who’s the brighter in the end – the mother or the son.[8]

But there was something more sinister than intellectual curiosity which led to communism. In his review of the film Bosley Crowthey in the New York Times wrote that intellectuals were seen as ‘dangerous perverters of youth.’[9] It was not only in the field of ideas that he was corrupt. John’s twisted relationship with his mother indicated murkier reasons for the descent into the abyss. Nora Sayre noted that John was deceitful and charming toward her and there was an undisguised hostility towards his father. His performance was as close as Hollywood would dare come to that of a homosexual.[10] The father looked on in disgust when he met his professor from his old University. In the early draft of the screenplay, Dan says to his wife: ‘Did you see that greeting? I thought they were going to kiss each other.’[11] John’s communism was the result of a combination of anti-athletic, intellectual and homosexual tendencies.

In the original screenplay, John’s mother was in a position to put John in prison for his communist activities. She could not bring herself to testify against John to the FBI and collapsed and was then put into a hospital. The draft screenplay was incomplete, but it did include notes of a speech where John renounced his communist past while making a speech to a high school. The speech, which incriminated him, was made even though the FBI was unable to convict him. John was arrested and taken to prison. In the final scene, he visited his mother in hospital and told her of his return to the ‘side of the angels’.[12]

The film required a different ending as Walker died before the end of My Son John. Some hasty rewriting was needed, and McCarey used some outtakes from Strangers On A Train given to him by director Alfred Hitchcock to spin out an ending.[13] To complete the film. John went through a remarkable conversion to capitalism at the end of the film and was immediately gunned down by his fellow communists beneath the Lincoln Memorial.

In the film from the 1930s through to the 1950s, the figure of Lincoln was used to bolster the political viewpoints of the filmmakers. Abraham Lincoln was the most deified on the Presidents in the American popular imagination. In Mr Smith Goes to Washington (1939), the dejected Smith returned to fight the corrupt politicians in the Senate after seeing a small child in front of the Lincoln Memorial. Director John Ford repeatedly used Lincoln as an icon of fundamental American wisdom in films such as The Iron Horse (1924) and Young Mr Linclon (1939). In Cheyenne Autumn (1964), the Secretary of State, played by Edward G. Robinson, looked at a picture of Lincoln, while pondering the fate of the Cheyenne Indians, and said ‘What would he do?’ and the problems of Cheyenne Indians were soon resolved. Lincoln was also used to support the closing anti-communist message in I Was a Communist for the FBI and The FBI Story (1958).

Lincoln was once again the icon of traditional American values. John’s death at the feet of the memorial showed that his political conversion and redemption was complete. He had paid his price for becoming a communist. In the original script he cried out: ‘I am a native American communist spy – and may God have mercy on my soul!’[14] The final film made John pay for his communism with his death. At the conclusion, a tape recording of his planned speech was played to a graduating class.

I was going to help to make a better world. I was flattered when I was immediately recognized as an intellect. I was invited to homes where only superior minds commuted. It excited my freshman fancy to hear daring thoughts … A bold defiance of the only authorities I’d ever known: my church and my father and my mother. I know that many of you have experienced that stimulation. But stimulants lead to narcotics. As the seller of habit-forming dope gives the innocent their first inoculation, with a cunning worthy of a serpent, there are other snakes waiting lying to satisfy the desire of the young to give themselves something positive…[15]

The concluding speech described communism as an addictive drug. This did not explain why John was able to break his addiction so easily. During his final speech a ray of light shines down on the stage indicating God’s approval, when John asked for God’s mercy, it was surely given.

The final speech was quite different form Hayne’s original script.[16] Hayne wanted to emphasise that the laws against communist agents were weak and the FBI could not have convicted John. He gave up any chance of escape and confessed that he had been passing secrets to the Russians.[17] McCarey, however wanted to drive home the inherent evil of communism. McCarey’s draft for John’s final speech was extremely close to the final film and it seemed that Walker’s death did little to change its direction.

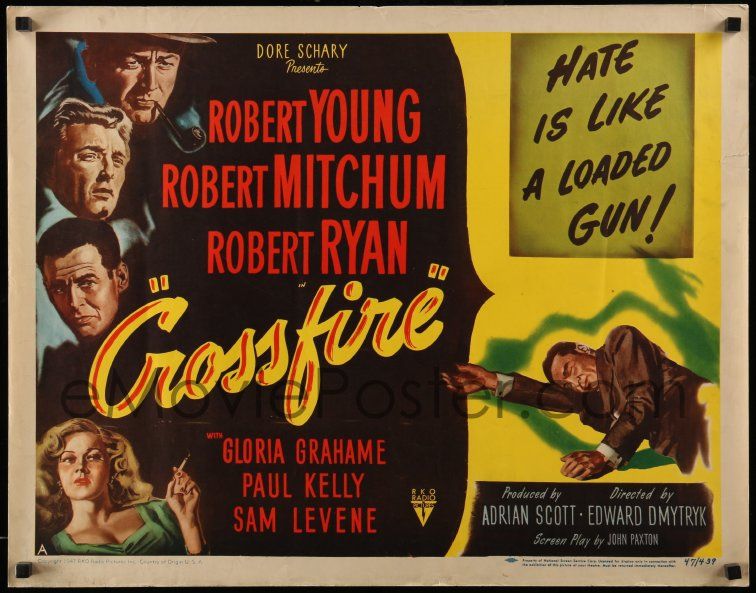

Once again, communism was expunged by a severe act of contrition. Both Robert Ryan in I Married A Communist and Robert Walker in My Son John had to perform this painful act to clear themselves of communism, just as those in Hollywood had to name names before the HUAC investigations in order to clear themselves. McCarey’s depiction of communism was the blackest of the 1950s. It was as an addictive drug peddled by intellectuals with homosexual tendencies to young impressionable minds. The thin academic air of college was a breeding ground for these delusions. Young people who wanted to do something positive may fall victim to its clutches. Yet the alternative in McCarey’s world was not much better. Violent and threatening, verging on psychotic, fathers and neurotic mothers were the all-American couple. These parents would sacrifice their children to the authorities through guilt by association. He film rationalized that the techniques used throughout America and Hollywood were necessary and desirable. It argued that being investigated was the same as being guilty; that authorities were impeccable in their research and pursuit of enemies and never made mistakes. John’s confession at the end of the film justified the physical and mental battering he had received from his mother, his father and the authorities. The confession was a justification of HUAC’s investigations and the stance taken by the studio heads. When the film was released, it was not surprising that DeMille said it was a great film and showed that McCarey was a great American.[18] The film was, however, universally condemned by film reviewers. My Son John represented the low water mark of Hollywood’s dealing with communism and the film did not make Variety’s list for the year despite some heavy advertising.[19] Most reviewers slammed the film, aside from Bosley Crowther in The New York Times who praised some aspects of it; but even he had grave concerns about its political dogmatism.

Bernard Dick focuses on Leo McCarey’s anti-communist film My Son John (1952) in some detail in his book The Screen is Red. The film’s production fell into a shambles with the death of lead actor Robert Walker, and an ending of sorts was created – with some unheralded assistance by Cecil B. DeMille and Alfred Hitchcock. The remaining film is uncomfortable to watch; it contains one disturbing scene in which an angry father attacks his communist son for laughing at his conservative jingoism. Despite the contrived conclusion, Dick describes McCarey as a master of plot resolution. He argues that McCarey gave viewers an ending that was “dramatic and reflective,” [117] providing an accurate description of America in the early years of the Cold War. His respectful analysis is at odds with both contemporary reviewers and later critics, who see it as a mixture of hysterical anti-communism tinctured with a vague homophobia – along with some disturbing ideas about motherhood.

[1] Ceplair and Englund, Inquisition, p. 259.

[2] My Son John, (d) Leo McCarey, Leo McCarey.

[3] Draft of final speech of My Son John, Cecil B. DeMille Archives, Box 439, Folder 10, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[4] A full discussion will be in the chapter on biblical epics.

[5] Quote from unnamed writer in Motion Picture Daily, 16 December 1949. Accounts of DeMille’s legendary treatment of writers can be found in Ring Lardner Jr., ‘The Sign of the Boss’, Screenwriter, November 1945, and Phil Koury, Yes, Mr DeMille, G.P.Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1976.

[6] Undated draft script of My Son John, Box 439, Folder 10, Cecil B. DeMille Archives, Box 439, Folder 10, Brighan Young University, Provo, Utah.

[7] William Manchester, The Glory and the Dream A Narrative History of America 1932 – 1972, Bantam, New York, 1975, pp. 625 – 626.

[8] New York Times, 18 March 1952. At the end of the original script, John asks his mother to bake cookies for him in prison.

[9] New York Times, 9 April 1952.

[10] Sayre, Running Time, p.96. Walker’s performance is close to his acclaimed role of Bruno in Strangers On A Train where again his performance had strong homosexual overtones. See Donald Spoto, Art Of Alfred Hitchcock, Dolphin, New York, 1976, p. 212 and for a differing view see Robin Wood, Hitchcock Film’s Revisited, Columbia University Press, New York, 1960, pp. 347 – 348. McCarey did claim that Hitchcock was a strong influence for the film, New York Times, 9 April 1952.

[11] Draft script of My Son John, p. 11 Box 439, Folder 10, Cecil B. DeMille Archives, Box 439, Folder 10, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Walker died after being prescribed some sedatives by doctors after emotional outbursts on the set of My Son John. He had a history of problems with alcohol and had suffered a nervous breakdown in the late 1940s. David Thomson, A Biographical Dictionary of the Cinema, Secker and Warburg, London, 1975, p. 595.

[14] Hayne, Donald John’s Speech, 2 June 1951, Cecil B. DeMille Archives, Box 439, Folder 10, Cecil B. DeMille Archives, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[15] My Son John, (d) Leo McCarey, Leo McCarey.

[16] Hayne, Donald John’s Speech, 2 June 1951, and Leo McCarey, Leo John’s Speech, 10 August 1951. Cecil B. DeMille Archives, Box 439, Folder 10, Cecil B. DeMille Archives, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[17]Undated draft script of My Son John, Ibid.

[18] Cecil B. DeMille to Leo McCarey, 3 April 1952. Cecil B. DeMille Archives, Box 439, Folder 10, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[19] The film’s advertising focused on a non-existent sex scene. The film was condemned by most film reviewers at the time. One belated defence of the film is in Leland A. Poague, The Hollywood Professionals: Wilder and McCarey, London, Tantry Press, 1980.