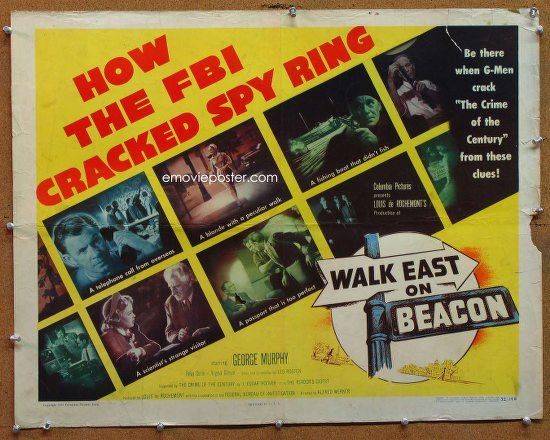

Image courtesy of eMoviePoster

Kevin Brianton

Senior Lecturer, La Trobe University

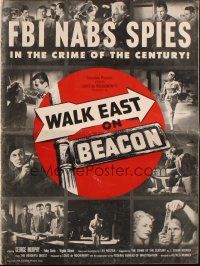

In 1951 FBI head J. Edgar Hoover was offered $15,000 for the rights to his article in Readers Digest which was based on the Fuchs-Gold case. Hoover had written – or it had been ghost written – the article called Crime of the Century which was published in Reader’s Digest in May 1951. British atomic scientist Karl Fuchs and American Harry Gold gave nuclear secrets to the Russians. Hoover refused the offer but granted the movie rights. His biographer Curt Gentry argued that Hoover refused the money because of the links between the case and the controversial Rosenberg trial. Gentry said that Hoover only arrested Ethel Rosenberg as a ‘lever’ to get Julius to confess. A decision he greatly regretted. The FBI’s anti-communist stance was shown in Walk East on Beacon .[1] The FBI is depicted in glowing – if somewhat – ridiculous terms throughout the film. The New York Times wrote: ” Chief J. Edgar Hoover’s story, “The Crime of the Century,” is an absorbing affair, as the law, utilizing such varied aids as hidden cameras, lip readers, television equipment and the Coast Guard, efficiently tightens the net around its elusive quarry. And, in the course of the chase, it becomes increasingly obvious that the F. B. I. cooperated in the production.” Like Big Jim McLain, which praised HUAC, Walk East on Beacon praised the Bureau. It was released with publicity material which said the country was in danger and citizens should report espionage, sabotage or subversive activities, the chattering of aircraft for flights over restricted areas, suspicious individuals loitering near restricted areas, foreign submarine landings, poisoning of public water supplies, possession and distribution of foreign-inspired propaganda, unusual fires or explosions affecting vital industry, suspicious parachute landings and possession of radioactive material.[2]

HUAC had begun its investigation by interviewing selected labor and industry leaders in the film industry in March 1947. Listening to anti-communist figures in Hollywood did not provide HUAC chair J. Parnell Thomas and investigator Robert Stripling with enough evidence to proceed with a full investigation. They needed the FBI, which had been building up a massive dossier of communist involvement in Hollywood over the past three years. At first, Hoover declined to support the venture because he did not want HUAC linked to the FBI, but Thomas and Stripling promised discretion when they contacted Los Angeles FBI agent R. B. Hood for support. Under this agreement, Hoover arranged to assist the committee on the basis that the FBI remained unidentified. With this assurance, Hoover testified to it in an open session on March 26, 1947, where he declared “the aims and responsibilities” of the HUAC and the FBI were the same: “The protection of the internal security of the Nation.” Hoover used the opportunity to argue that the Communist Party was penetrating many “public opinion mediums,” particularly the film industry, and that it would achieve its goal of capturing American institutions through infiltration of the unions and creative outlets. Hoover said, “I would have no fears if more Americans possessed the zeal, the fervor, the persistence and the industry to learn about this menace of Red fascism. I do fear for the liberal and progressive who has been hoodwinked and duped into joining hands with the communists.” Hoover’s testimony to HUAC was a clear blurring of the lines between liberals and radicals. Congress further ordered that 250,000 copies of Hoover’s address were to be printed and distributed. The FBI and HUAC were now allies. The FBI would gather the evidence and the committee would disclose it. By making films about these entities were certainly trying to appease their new political masters.[3]

The plot was the unlikely plan about the blackmail and kidnapping of a scientist working on an important new computer called Falcon. Throughout the film, the FBI was depicted as a highly efficient organisation following up hundreds of leads. One such lead gives the name of a possible communist agent. The suspect was followed by FBI agents to the Polish freighter where he was substituted by an agent from Moscow who was able to use his papers. The Russian agent in turn was then followed by a series of FBI agents. The communists were involved in a complex plot to extort important mathematical formulae from a scientist Dr Krayer. The scientist’s son had been captured in East Germany and the communists told Krayer that he would be safe provided that the critical information he was working on was handed on to their agents.

Communists who left the party or who pretended to leave were subject to constant recall. One party member was threatened with blackmail after he was tracked down by his colleagues. He said that it was impossible to leave and informing to the FBI meant death.[4] Those who pretended to leave the party were only sleepers waiting to be activated by Moscow. Those people lived and worked in the community and could not be detected. Nevertheless, the FBI appeared as a ruthlessly efficient operation with thousands of agents working around the clock to stop subversion. The audience was reminded that foreign agents in the United States were given great freedoms. A list of agents who have been ‘sleeping’ for years before being activated was repeatedly shown.

Most of the film was about setting up an elaborate web to send the information to Moscow. The web included exchanging papers in parks, taxi cabs, airport lockers and other means. When this complex apparatus fell apart, the communists adopted the more direct route of kidnapping the scientist and smuggling him out of the country. The film ended with the capture of all the communist agents, but with a warning that hundreds of other plots were being hatched across the United States. The audience was told that a small group of highly trained communist agents can do the damage of millions. Yet, as critic Nora Sayre points out, these communist agents were grossly incompetent, allowing themselves to be followed, bugged and filmed at every turn.[5] When one communist courier was told that he was being followed by the FBI, he immediately walked over to the agent and said: ‘You’re FBI and I know you are following me.’[5] The stupidity of the communists may be explained by the scientist who attacked the communists saying that ‘minds in chains cannot think.’[6]

The

film claimed that the United States was blessed with great freedoms and this

could lead to its undoing. The message

of too much freedom, and freedoms being abused, was repeated in The FBI Story (1958) which also had the

backing of FBI head J. Edgar Hoover and Big

Jim McLain (1951). Despite those

comments, communist agents appeared to be subject to intensive surveillance

around the clock. They were filmed in parks, bugged in their houses, have their

mail opened and were constantly followed.

All this was in response to a single anonymous tip that a person may be

a communist. The FBI said that hundreds

of tips were received every day giving rise to an image of surveillance in the

United States of Orwellian dimensions. Walk East on Beacon was an image of

society where the only way to survive was in the hands of the FBI. Freedoms had to be given up to retain

freedom. The film was ranked 88th

in the Variety rankings taking in

$1.3 million.[7]

[1] See Curt Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and His Secrets, Norton, New York, 1991 and Ronald Radosh and Joyce Milton, The Rosenberg File: A Search For Truth, Vintage, New York, 1984.

[2] Sayre, Running Time, pp. 92 – 93.

[3] Athan G. Theoharis, The FBI & American Democracy: A Brief Critical History (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004), 89. O’Reilly, Red Menace, 89–91. Ellen Schrecker, The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents (New York: Palgrave, 2002), 154–159.

[4] Walk East on Beacon, (d) Alfred Werker, Leo Rosten.

[5] Sayre, Running Time, p. 91.

[6] Walk East on Beacon, (d) Alfred Werker, Leo Rosten.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Variety, 7 January 1953.

I find this historical perspective fascinating.

LikeLike